Musical Theory IV

Triads

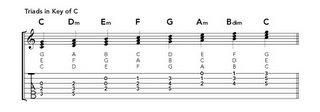

Last week's post on modes was quite complex, so now we'll relax a little a cover the idea of triads. Up until this point, we have been dealing with theory one note at a time. But this is obvioulsy not how music is played. What happend when more than one note is played simulatneously? We get a chord. One of the very basic, yet important, chords is the triad.

Last week's post on modes was quite complex, so now we'll relax a little a cover the idea of triads. Up until this point, we have been dealing with theory one note at a time. But this is obvioulsy not how music is played. What happend when more than one note is played simulatneously? We get a chord. One of the very basic, yet important, chords is the triad.

Triads are a "stack", if you will, of three notes that are played simultaneously. In the major triad, the basic form is the triad name, one third about that (or 4 semitones) and one fifth above the triad name (or 7 semitones). More simply, this would be the first, third and fifth notes of the major scale of the same name. For example, a C major triad would be the first, third, and fifth notes of the C major scale: C E G. Another example, the Bb major triand would be the first, third, and fifth notes of the Bb major scale: Bb D F. Minor triads work on the same principle, only they are based on the first, third, and fifth notes of the minor scale with the same name. (For example C minor triad would be C Eb G and Bb minor triad would be Bb Db F.) A major triad can be converted into a minor triad by flatting the third one semitone. For example, the D major triad is D F# A. To obtain the D minor triad, all we need to do is flat the third. Therefore, F# would then become F, and we would have D F A, our D minor triad.

Of course the notes of each triad don't have to be played in this rigid position of first, third, fifth, from bottom to top, as close together as you can get them. The notes can be played in any order, and these differing orders are called inversions. The basic position of a triad is call root position. This is because the name of the triad is at the bottom of the chord. In our D major triad, D and then the F# immediately above it, and then the A immediately above that F# would be the root position. The next ordering of notes is the first inversion. This may be obtained by taking the first, or the bottom note of the triad in root position, and putting it on the top. Thus with our D major triad, the first inversion would be F# on the bottom, then the next A up from that F#, and then the next D above that A. Second inversion is taking the bottom note of the first inverstion and placing it on top. In our D major chord, A on the bottom, the next D directly above that, and finally the next F# above that D on the top. There is no third inversion, because if you take the bottom note of the second inversion and place it on the top of the chord, you get the root position again. Therefore with a triad there are three positions, root, first inversion, and second inversion.

The root and inversions of a minor triad work the same way, but with the notes of the minor chord.

I have described these triads as all played within the same octave, or closed triads. But, there are many octaves in music and nothing to restrict us to only one while playing a chord. If you spread the notes out over several octaves, you have an open triad. For example, with our D major triad we could pick and F# as low on the piano as we can go, the D next to middle C, and the highest A possible. Obviously this would be silly to play this way, but it is a valid open triad.

Wasn't so painful this week, was it?

Quis Question #2

This week, as we are dealing with Buddy Rich, the question will be drum related. Name 3 drum rudiments, and indicate one possible sticking for each.

Last week's post on modes was quite complex, so now we'll relax a little a cover the idea of triads. Up until this point, we have been dealing with theory one note at a time. But this is obvioulsy not how music is played. What happend when more than one note is played simulatneously? We get a chord. One of the very basic, yet important, chords is the triad.

Last week's post on modes was quite complex, so now we'll relax a little a cover the idea of triads. Up until this point, we have been dealing with theory one note at a time. But this is obvioulsy not how music is played. What happend when more than one note is played simulatneously? We get a chord. One of the very basic, yet important, chords is the triad.Triads are a "stack", if you will, of three notes that are played simultaneously. In the major triad, the basic form is the triad name, one third about that (or 4 semitones) and one fifth above the triad name (or 7 semitones). More simply, this would be the first, third and fifth notes of the major scale of the same name. For example, a C major triad would be the first, third, and fifth notes of the C major scale: C E G. Another example, the Bb major triand would be the first, third, and fifth notes of the Bb major scale: Bb D F. Minor triads work on the same principle, only they are based on the first, third, and fifth notes of the minor scale with the same name. (For example C minor triad would be C Eb G and Bb minor triad would be Bb Db F.) A major triad can be converted into a minor triad by flatting the third one semitone. For example, the D major triad is D F# A. To obtain the D minor triad, all we need to do is flat the third. Therefore, F# would then become F, and we would have D F A, our D minor triad.

Of course the notes of each triad don't have to be played in this rigid position of first, third, fifth, from bottom to top, as close together as you can get them. The notes can be played in any order, and these differing orders are called inversions. The basic position of a triad is call root position. This is because the name of the triad is at the bottom of the chord. In our D major triad, D and then the F# immediately above it, and then the A immediately above that F# would be the root position. The next ordering of notes is the first inversion. This may be obtained by taking the first, or the bottom note of the triad in root position, and putting it on the top. Thus with our D major triad, the first inversion would be F# on the bottom, then the next A up from that F#, and then the next D above that A. Second inversion is taking the bottom note of the first inverstion and placing it on top. In our D major chord, A on the bottom, the next D directly above that, and finally the next F# above that D on the top. There is no third inversion, because if you take the bottom note of the second inversion and place it on the top of the chord, you get the root position again. Therefore with a triad there are three positions, root, first inversion, and second inversion.

The root and inversions of a minor triad work the same way, but with the notes of the minor chord.

I have described these triads as all played within the same octave, or closed triads. But, there are many octaves in music and nothing to restrict us to only one while playing a chord. If you spread the notes out over several octaves, you have an open triad. For example, with our D major triad we could pick and F# as low on the piano as we can go, the D next to middle C, and the highest A possible. Obviously this would be silly to play this way, but it is a valid open triad.

Wasn't so painful this week, was it?

Quis Question #2

This week, as we are dealing with Buddy Rich, the question will be drum related. Name 3 drum rudiments, and indicate one possible sticking for each.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home