Musical Theory I

The basics about scales and key signatures:

A scale is a sequence of notes based on the idea of semitones and tones. A tone is a way of measuring the difference in pitch between two notes. A semitone is half a tone. A scale is a sequence of 8 notes (the first and the last being the same note) which are a set interval apart from one another. These set intervals are:

I -tone- ii -tone- iii -semitone- IV -tone- V -tone- vi -tone- vii -semitone- VIII (I)

For a major scale (e.g. C D E F G A B C)

I -semitone- ii -tone- iii -tone- IV -tone- V -semitone- vi -tone- vii -tone- VIII (I)

For a (natural) minor scale (e.g. A B C D E F G A)

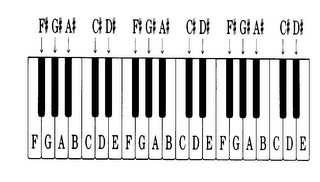

This can be best seen on a piano keyboard:

As you can see by looking at the examples for the two given scales above, tones occur where there is a black key inbetween two white keys, and semitones occur where this black key is missing. A semitone by definition on a keyboard would be two notes that are directly next to eachother (i.e. not seperated by another key). Therefore, from C to C# on this keyboard would be a semitone, as would B to C. On a guitar, the distance between two adjacent frets is a semitone. If you skip a fret, that interval is a tone.

As you can see by looking at the examples for the two given scales above, tones occur where there is a black key inbetween two white keys, and semitones occur where this black key is missing. A semitone by definition on a keyboard would be two notes that are directly next to eachother (i.e. not seperated by another key). Therefore, from C to C# on this keyboard would be a semitone, as would B to C. On a guitar, the distance between two adjacent frets is a semitone. If you skip a fret, that interval is a tone.

These intervals work out fine for a major scale using the white keys from C to C (the C major scale), but what if we wanted to play a major scale from the notes D to D (the D major scale)? Our semitones and tones would be misalligned if we just used white keys. This is why sharps (#) and flats (b) exist. [Note: A flat usually has a more pointed bottom on it, but it does closely resemble a lower case "b", so for our purposes here we will use "b"]

A sharp is defined as a semitone above the given note. For example, D# would be the next key to the right of D, which would be the black key we can call D#. In a similar respect, E# would be the next key to the right of E, which is a white key already named F. Thus F = E#. A flat is defined as a semitone below the given note. For example Db would be the next key to the left of D, which would be the black key we can call Db. You will also notice that in the above diagram this key is labelled C#. That is because every key is to the right and to the left of another key, so every note is a sharp and a flat. Db = C#. Similarly, Cb would be the key to the immediate left of C, which is a white key already named B. Thus, Cb = B.

These sharps and flats, also referred to as "accidentals", can be used to adjust our scale from D to D so that it is a proper major scale by definition. We would raise the third and seventh notes (F and C, respectively) by a semitone in order to obtain our D major scale. Thus the "key of D major" has F# and C# in it. A key signature indicates which notes need to be sharped or flatted to make sure the scale has the correct intervals between each of it's notes. A piece of music is in a particular key when that piece uses (only) notes from the scale which shares a name with the key.

But, let's face it, to figure out all of this semitone and tone stuff every time we want to play a certain scale would be a hassle. There is an easy way to remember which major scales have which key signatures.

When read from left to right, the first letter of each word indicates a sharp. This is the order in which sharps occur (FCGDAEB). When read from right to left, the first letter of each word indicates a flat. This is the order in which the flats occur (BEADGCF). Then you only need remember how many flats or sharps each major key has.

Sharp Key------# of Accidentals------Flat Key

C---------------------none------------C

G----------------------1--------------F

D----------------------2--------------Bb

E----------------------3--------------Eb

A----------------------4--------------Ab

B----------------------5--------------Db

F#---------------------6--------------Gb

C#---------------------7--------------Cb

Minor keys derive their key signatures from a relative major. Minor keys and their respective key signatures will be covered next week.

A scale is a sequence of notes based on the idea of semitones and tones. A tone is a way of measuring the difference in pitch between two notes. A semitone is half a tone. A scale is a sequence of 8 notes (the first and the last being the same note) which are a set interval apart from one another. These set intervals are:

I -tone- ii -tone- iii -semitone- IV -tone- V -tone- vi -tone- vii -semitone- VIII (I)

For a major scale (e.g. C D E F G A B C)

I -semitone- ii -tone- iii -tone- IV -tone- V -semitone- vi -tone- vii -tone- VIII (I)

For a (natural) minor scale (e.g. A B C D E F G A)

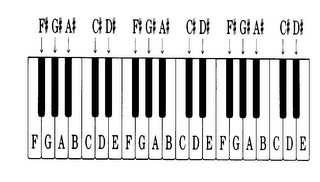

This can be best seen on a piano keyboard:

As you can see by looking at the examples for the two given scales above, tones occur where there is a black key inbetween two white keys, and semitones occur where this black key is missing. A semitone by definition on a keyboard would be two notes that are directly next to eachother (i.e. not seperated by another key). Therefore, from C to C# on this keyboard would be a semitone, as would B to C. On a guitar, the distance between two adjacent frets is a semitone. If you skip a fret, that interval is a tone.

As you can see by looking at the examples for the two given scales above, tones occur where there is a black key inbetween two white keys, and semitones occur where this black key is missing. A semitone by definition on a keyboard would be two notes that are directly next to eachother (i.e. not seperated by another key). Therefore, from C to C# on this keyboard would be a semitone, as would B to C. On a guitar, the distance between two adjacent frets is a semitone. If you skip a fret, that interval is a tone.These intervals work out fine for a major scale using the white keys from C to C (the C major scale), but what if we wanted to play a major scale from the notes D to D (the D major scale)? Our semitones and tones would be misalligned if we just used white keys. This is why sharps (#) and flats (b) exist. [Note: A flat usually has a more pointed bottom on it, but it does closely resemble a lower case "b", so for our purposes here we will use "b"]

A sharp is defined as a semitone above the given note. For example, D# would be the next key to the right of D, which would be the black key we can call D#. In a similar respect, E# would be the next key to the right of E, which is a white key already named F. Thus F = E#. A flat is defined as a semitone below the given note. For example Db would be the next key to the left of D, which would be the black key we can call Db. You will also notice that in the above diagram this key is labelled C#. That is because every key is to the right and to the left of another key, so every note is a sharp and a flat. Db = C#. Similarly, Cb would be the key to the immediate left of C, which is a white key already named B. Thus, Cb = B.

These sharps and flats, also referred to as "accidentals", can be used to adjust our scale from D to D so that it is a proper major scale by definition. We would raise the third and seventh notes (F and C, respectively) by a semitone in order to obtain our D major scale. Thus the "key of D major" has F# and C# in it. A key signature indicates which notes need to be sharped or flatted to make sure the scale has the correct intervals between each of it's notes. A piece of music is in a particular key when that piece uses (only) notes from the scale which shares a name with the key.

But, let's face it, to figure out all of this semitone and tone stuff every time we want to play a certain scale would be a hassle. There is an easy way to remember which major scales have which key signatures.

"Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle"

When read from left to right, the first letter of each word indicates a sharp. This is the order in which sharps occur (FCGDAEB). When read from right to left, the first letter of each word indicates a flat. This is the order in which the flats occur (BEADGCF). Then you only need remember how many flats or sharps each major key has.

Sharp Key------# of Accidentals------Flat Key

C---------------------none------------C

G----------------------1--------------F

D----------------------2--------------Bb

E----------------------3--------------Eb

A----------------------4--------------Ab

B----------------------5--------------Db

F#---------------------6--------------Gb

C#---------------------7--------------Cb

Minor keys derive their key signatures from a relative major. Minor keys and their respective key signatures will be covered next week.

10 Comments:

Thanks for the theory lesson. It's all very clearly written. I never learned that Charles Goes Down thing and was forever mystified by how my teacher could glance at the key signature and know which key we were singing in.

Here's what a flat sign looks like, if anyone's dying to know. . .

Thanks, Jack. This is really great.

By ing, at Mon Dec 19, 10:56:00 AM MST

ing, at Mon Dec 19, 10:56:00 AM MST

No problem ing.

Actually, I really like theory. It's so mathematical and structured and makes a lot of sense.

I've also spent a lot of time figuring it out, and so enjoy explaining it to people. One of these days, I might even write a book on musical theory.

Jack

P.S. If you want to know an even better secret about key signatures:

SHARP KEYS: The seventh (second last) note of the scale is the last sharp in the sequence when you recite "Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle". For example, if you choose the key of E, the note before it is D (the seventh) and the sharps in the key are F C G D, or "Father Charles Goes Down".

FLAT KEYS: With the exception of the key of F, which one just has to memorize as Bb, the name of the key is the second last flat in the key signature, when reciting "Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles Father". So for example, if you pick the key of Ab, then the flats are B E A D or "Battle Ends And Down".

All sorts of nifty patterns.

*grin*

Jack

By Rose, at Mon Dec 19, 09:14:00 PM MST

Rose, at Mon Dec 19, 09:14:00 PM MST

A very good idea to include musical theory. I went to the music institute where you had to learn three levels of music theory (along with three levels in a given instrument - mine was the violin/viola), but looking forward to the more advanced stuff about jazz theory!

By E.L. Wisty, at Tue Dec 20, 03:53:00 AM MST

E.L. Wisty, at Tue Dec 20, 03:53:00 AM MST

Heh, I'm slow on the uptake and yet I think I'm getting it. The funny thing is, when I have a breakthrough with this stuff, I realize that it's something I already know! I'm talking about how it relates to sound. I know the sound part. Like when I was reading about scales.

You have to realize, this is worse than someone being dyslexic trying to

read, for me to transfer music to written language.and to to read theat language and understand how it's trying to sound. But I'm getting it, for the most part. We are talking about predominantly piano right now, right? For sharps and flats? I have questions but I don't like sounding dumb all the time.Most people would rather have their fingernails pulled out them let on that they don't know something. I've noticed.

So sharps and flats came about for the need of them on piano?I understand the part about the need for them. I think. But am I confusing myself because I'm trying to transfer some of this knowledge

to my guitar? The scale thing, I understood that. But now my question is,does Father Charles Goes Down

And Ends Battle work on guitar?

I'm starting to wonder if I need to

do some pre-research before reading this particular blog. I'm just not the most educated person here, at all. Probably the least.I feel so aware of it right at this moment, lololollolol. :)

But what I am getting is great, Jack. I've already learned a lot

just from the most minor things, like the sharp and flat smybols. Yep, it's that bad.It's like, oh, so that's what those little symbols mean! I've seen those! I don't actually read music ( wince) Kind of, anyway. I'm actually starting to, here.

By Nabonidus, at Tue Dec 20, 02:27:00 PM MST

Nabonidus, at Tue Dec 20, 02:27:00 PM MST

Hey Jack!

I just came to back to say,( and this is so weird of a coincidence), I'm goingto repost some stuff I wrote a couple of months back,something like that. I wrote a 2 part post about how I have trouble reading music, and translating it. Like I said, it's kinda weird coincidence. I don't think you were reading my blog yet. I'd been inspired by PT, remembering how he'd played French horn. Reminded me that I used to play.So I'm going to go repost those, just so you can read them and go " Uh oh.This is an exceptionally bad case here."

xoxoLisa

By Nabonidus, at Tue Dec 20, 02:40:00 PM MST

Nabonidus, at Tue Dec 20, 02:40:00 PM MST

nabonidus,

It's easier to explain on the piano, cause the piano is nicely laid out and very visual. But yes, it works on a guitar as well.

Each fret on the guitar as you head up the neck increases the pitch of the string by a semitone.

With standard guitar tuning, the strings (when played open) are:

E A D G B E

This means that the first fret on an E-string will be a semitone higher than E, E# (better known as F). The second fret will be a semitone higher than F, or F#. Much like the piano, F# is also a semitone lower than the fret above it (G), so it can also be referred to as Gb. F# = Gb.

It follows for all the rest of the strings.

If you want to play a scale on the guitar, play the same notes in sequence as you would on a piano, only you have to find them on the guitar.

Oh yes, and don't play it all on one string, that is silly. :) If you were to play the E major scale, which our good friend Father Charles tells us has F#, C#, G#, D# as a key signature, you would start with the low E string.

Then, we must next find F#, which will be 2 semitones (2 frets) higher.

G# is another 2 semitones (frets) from F#.

Now we want to play A. We could simply play one fret higher than G#, but this is redundant, as you already have a string that is tuned to A. (And not just any A, that specific A!)

So then you would move on to the next string.

And so forth...

I don't know if this is terribly helpful... I know how a guitar works, I have tuned them, repaired them, etc. But in all honesty I couldn't play a guitar to save my life.

The short version of what I mean to say is: "Yes, it works the same on guitar as it does on piano."

Windbag:

Jack

By Rose, at Tue Dec 20, 05:53:00 PM MST

Rose, at Tue Dec 20, 05:53:00 PM MST

Jack:

This is like math. You lost me on that pattern thing (I so suck at math!).

The first rule says that you can look at the last sharp in a key sig, go up one note, and you'll have the key -- right?

The second rule says that excepting the key of F, the key is the same note as the second-to-last flat in the key sig -- did I get it?

Now here's a dumb question: if the sharps in the key sig are F C G D, are we in the key of E, or are we in the key of E sharp?/

By ing, at Wed Dec 21, 10:14:00 AM MST

ing, at Wed Dec 21, 10:14:00 AM MST

ing,

We are in the key of E, as there is no E# in the key signature. :)

You have no idea how many students have asked me that exact same question!

Jack

By Rose, at Wed Dec 21, 05:02:00 PM MST

Rose, at Wed Dec 21, 05:02:00 PM MST

That was excellent, Jack, I understood! I admit I lagged coming back to this blog because my head hurt and I was slightly afraid I wouldn't get it.

But I did, and once again, your teaching is kind of stuff where I say " Oh, I was doing a lot of that already, I just didn't know what it was called." Hmmm...

And Ing, I didn't think that was a dumb question. :)

By Nabonidus, at Thu Dec 22, 07:29:00 PM MST

Nabonidus, at Thu Dec 22, 07:29:00 PM MST

nabonidus,

Don't be afraid that you won't "get it". If you don't get something, just ask questions, or tell me you don't get it and I'll try and explain it better another way.

We're all here to learn, including me! Questions make me go and look things up, which is good. Oh, and corrections are welcomed. Or additions like ing showing what a flat looks like.

:D

Jack

By Rose, at Thu Dec 22, 10:23:00 PM MST

Rose, at Thu Dec 22, 10:23:00 PM MST

Post a Comment

<< Home