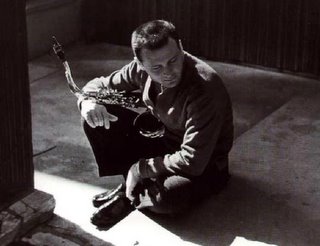

Stan Getz

[NOTE: The ninth post in the Musical Theory series of posts can be found below]

Name: Stanley Gayetzky

Born: February 2, 1927

Died: June 6, 1991

Instrument: Saxophone

Beginnings of Obsession:

Stan Getz first picked up the Sax at the age of 13, after expirementing with a number of other instruments, and fell instantly in love. The instrument was a present from his father, and sparked a powerful obsession in Stan that would stay with him right up until they day he died. Three years later, at the age of 16, Stan got picked up by Jack Teagarden. Over the next 3 years he played with numerous bands including Stan Kenton, Jimmy Dorsey, and Benny Goodman, but finally made his name with the Woody Herman band from 1947 to 1949. His lyrical solos an immaculate tone gained him much attention, and with his solo on Early Autumn. Stan's mastery of the instrument was apparent through the subtle touches he used to colour his work. He was able to create melodic solos that were mellow, without getting locked into the "foo-foo" sax sound. Soft articulation and breath were paired with sharp, pure tone in a way that accentuated the melodic line. Everything was used in perfect moderation, compiled to create a stunning, and extremely memorable whole. When asked about how he developed his sound, later on in life, he replied:

"I never consciouly tried to conceive of what my sound should be. I never said, 'I want this kind

of sound!' I believe it was because of the bands I played with from the ages of 15 to 22. The first one was Jack Teagarden, who we all know played trombone, but his sound was so great, so...(pause) sort of legitimate, and effortless. I never tried to imitate anybody, but when you love somebody's music, you're influenced. Then I was with Benny Goodman when I was 18 and I believe his sound had an influence on me; such a good sound that he had in those days, you know? And, in-between I heard Lester Young of course, and it was a special kind of trip to hear someone like Lester, who sounded so good and almost classical in a warm way. He took so much of the reed out of the sound. I really don't know how I developed my sound, but it comes from a combination of my musical conception and no doubt the basic shape of the oral cavity. I did always try to get as much of the reed out of the sound as I could."

of sound!' I believe it was because of the bands I played with from the ages of 15 to 22. The first one was Jack Teagarden, who we all know played trombone, but his sound was so great, so...(pause) sort of legitimate, and effortless. I never tried to imitate anybody, but when you love somebody's music, you're influenced. Then I was with Benny Goodman when I was 18 and I believe his sound had an influence on me; such a good sound that he had in those days, you know? And, in-between I heard Lester Young of course, and it was a special kind of trip to hear someone like Lester, who sounded so good and almost classical in a warm way. He took so much of the reed out of the sound. I really don't know how I developed my sound, but it comes from a combination of my musical conception and no doubt the basic shape of the oral cavity. I did always try to get as much of the reed out of the sound as I could."Cool Jazz:

During the 1950's, Stan became quite popular playing in the world of Cool Jazz. Even Charlie Parker, the saxophonist that every sax player wants to sound like, said of Stan "Let's face it. We would all play like him, if we could." While playing in this genre, it became apparent that Stan was also a highly intellectual player. A good example of this is his work on the song Crazy Chords, in which he takes his band through a whirlwind of keys, some of which no sax player in their right mind would ever dream of touching. The stunning part is how effortless he makes it all sound, all the while maintaining his purity of tone. Unfortunately, as happened to most Cool Jazz or Bebop players, Stan adopted a problem drug habit. Moving to Copenhagen to deal with his problem, Stan go to play with European Jazz musicians such as Lars Gullin, Martial Solal, and Bengt Hallberg, which most likely further contributed to his unique sound.

Bossa Nova:

Upon returning to the United States, Stan teamed up with guitarist Charlie Byrd who had just returned from Brasil. It was during this time that Stan put out one of his most popular tunes, Desafinado on the Jazz Samba album. This was his brief foray into popular culture, as a Bossa Nova craze swept over the states. Where to go from here? Down to Brasil to work with the source itself: Antionio Carlos Jobim and the Gilbertos. Jobim was a legend in the area of Bossa Nova, and Stan helped to popularize it through the Grammy winning song Girl From Ipanima, release in 1963. (The file is available below.) Bossa nova is a derivative of the Samba style, but less percussive and more harmonically complex. It was this harmonic complexity that appealed to many Cool Jazz players at the time. (The use of sevenths and extended chords.) Bossa nova would be the genre that Stan would be most associated with. In his later years, Stan would still enjoy playing in the bossa nova style, although he would try to play more obscure tunes, rather than the almost cliche Girl From Ipanima.

Brief Electricity:

Stan Getz had a brief affair with fusion and electronic jazz, but was panned by the press for it and quickly decided it was not the genre for him. His passion and love of the saxophone stayed with him in his later years, all through his battle with liver cancer. Despite his success and "god-like" status in the music world, Stan was a very kind and open man. Easy to get along with, he enjoyed telling stories of past gigs, and the odd dirty joke. When he found out he had cancer, he quit smoking, drinking, and any of the drugs that had been left over from before his trip to Copenhagen. Before he died, Stan was taking herbs, eating health food, and receiving special massages every day. Yet, he still was obsessed with his love of music, and performed, even if it would mean literally collapsing from exhaustion backstage after a show. His morale was good, even up until the day he died. Who could blame the man? He was able to spend his life doing what he loved, and I'm sure that his young model girlfriend, Samantha, also contributed to his mood. He lived what he loved, and died a happy man in June of 1991. We should all be so lucky.

Stan Getz had a brief affair with fusion and electronic jazz, but was panned by the press for it and quickly decided it was not the genre for him. His passion and love of the saxophone stayed with him in his later years, all through his battle with liver cancer. Despite his success and "god-like" status in the music world, Stan was a very kind and open man. Easy to get along with, he enjoyed telling stories of past gigs, and the odd dirty joke. When he found out he had cancer, he quit smoking, drinking, and any of the drugs that had been left over from before his trip to Copenhagen. Before he died, Stan was taking herbs, eating health food, and receiving special massages every day. Yet, he still was obsessed with his love of music, and performed, even if it would mean literally collapsing from exhaustion backstage after a show. His morale was good, even up until the day he died. Who could blame the man? He was able to spend his life doing what he loved, and I'm sure that his young model girlfriend, Samantha, also contributed to his mood. He lived what he loved, and died a happy man in June of 1991. We should all be so lucky.